Kinematic Model

|

Kinematic Model |

|

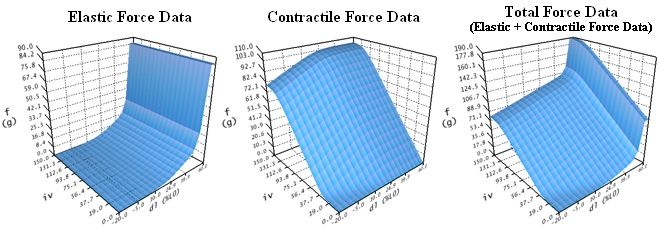

In order to be able to completely simulate a mechanical system, apart from geometrical structures, the simulation of forces is also needed. The force development of extraocular muscles is described by an isolated force model, providing specific behavior patterns for each muscle. The structure of the model orients itself on already existing model types for the skeletal musculature. Here the muscle function is divided into elastic (passive) and contractile (active) force development. Elastic forces are developed due to stretch and compression of the muscle, while contractile forces always presuppose a neurophysiological activation potential. The resulting total force function adds up contractile and elastic force functions and simulates the actual impact of a muscle.

Muscle Force Simulation of Lateral Rectus Muscle (Based on Orbit™, See [Miller, 1999])

The functions shown in this figure describe the static force development of a muscle concerning a well-defined force-length-innervation relationship. While the elastic force development (f in grams) is defined exclusively in dependence of the length variation of a muscle (dl in percent of L0), the contractile force function (f in grams) is additionally dependent on the innervation (iv). The muscle force simulation of all other extraocular muscles is implemented as relative scaling of the data displayed in this figure. The underlying data were defined according to research of Miller and Robinson.

The geometrical model and the model for the muscle force simulation described so far are now connected by the introduction of a kinematic model. This kinematic model is responsible for the transmission of forces in the geometrical model. To achieve this, each muscle's rotation angle around its geometrical axis is put in relation to the predicted force development. The result is a rotation axis with an associated rotation angle, which describes the current mechanical impact of all six eye muscles in a certain gaze position. If a rotation of the globe into the predicted direction is carried out, again all components of the geometrical model and of the muscle force simulation change. As a result of the change in the geometrical model, the muscle force distribution also changes and due to the passive length change of the muscles the muscle force functions are modified and transitively result in a new force distribution. This process continues until a stable eye position can be achieved. Such a stable eye position is characterized by a force equilibrium of all six muscles.

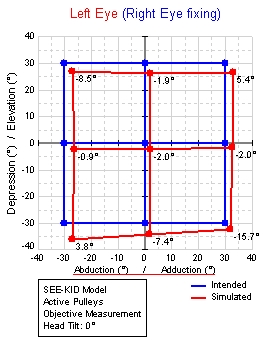

With the help of this simulation technique, the problems of the forward and inverse kinematics can be solved. The forward kinematic finds the resulting gaze position with given innervations for all six eye muscles, whereby the inverse kinematic derives the innervations for all six eye muscles from a given gaze position. If these two methods are now combined, a test for the binocular examination of eye movement disorders can be simulated. The SEE++ system simulates the Hess-Lancaster test by displaying the standard gaze positions of one eye next to the pathological deviations of the other eye in different colors.

Hess Test with Standard Gaze Positions of a Non-Pathological

(Right) Eye (Dark or Blue) and Gaze Positions of a

Pathological Left Eye (Bright or Red).

For each gaze position, the innervation pattern of all eye muscles of the fixing non-pathological eye is determined and subsequently passed to the pathological eye (Hering's law) in order to determine its resulting gaze position. The innervations are only defined for the agonistic muscles, the antagonistic innervations have to be calculated by application of a reciprocal innervation function (Sherrington's law). The result of the test can easily be seen by comparing the standard gaze positions with the pathological gaze positions of the examined eye: Slight diplopia in primary position, hyperfunction of the left eye in depression and abduction of the right eye, etc.

On basis of these models and their parameters, a pathological situation and/or a surgery is simulated. The changes in geometry directly affect the currently used geometrical model, as for example when transposing an insertion, the new insertion coordinates are directly applied and thus a new direction of pull of the muscle is defined. How the new muscle path will affect the mechanical behavior of the eye is highly dependent on the particular geometrical model that is used. For example, the string model provides a significantly "worse" anatomical representation than the tape model of Robinson.