Pulley Models

|

Pulley Models |

|

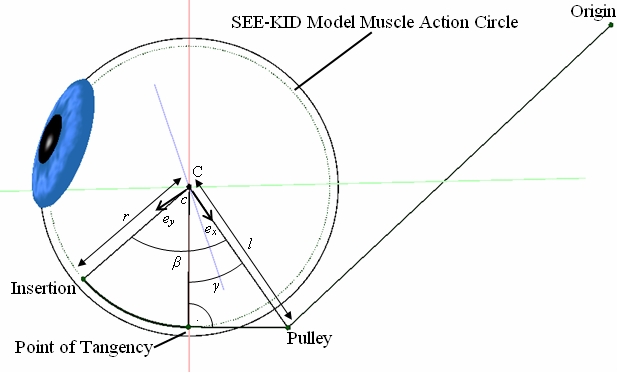

The SEE++ system implements 3 models that consider pulleys, namely the SEE-KID model, the SEE-KID active pulley model and the Orbit model. These models define a pulley as an additional point for the geometrical definition of the muscle path. The pulleys as functional elements were discovered by Miller and Demer in 1989 and were measured three-dimensional with the help of MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and histological research. By the additional introduction of a pulley, a muscle hardly moves in the rear area of the orbita when the eye changes its position. The functional origin, i.e. the point of interest for the calculation of the main muscle action, is now not the anatomical origin, but the pulley. This causes a strong stabilization of the muscle in its path from the pulley to the insertion with the effect that the muscle in extreme gaze position maintains its main direction of pull.

Muscle Path of the SEE-KID Model

The models that consider pulleys provide the best predictions in regard to their geometrical behaviour in comparison with clinical data so far. The finding that a pulley as supporting ligament can be seen as an additional anatomical structure of the eye also solved many open questions regarding clinical, surgical aspects. Furthermore, pulleys are elastically coupled to the orbital wall and, in far tertiary gaze positions, they can slightly shift in order to affect and correct the muscle path (basis of the "Functional Topography"). This characteristic contributes substantially to the mechanical stabilization of muscle action and, as a consequence, the entire oculomotor apparatus.

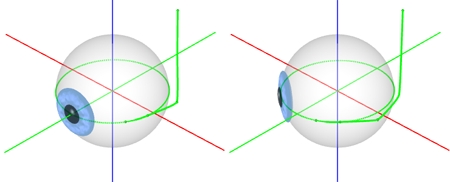

Muscle Path of the SEE-KID Active Pulley Model in Primary (Left) and Secondary Gaze Position (Right)

The SEE-KID active pulley model, in contrast to the SEE-KID model and the Orbit model, does not simulate the pulleys as fixed static elements, but as elements which actively move with the eye. So for example the pulley of the lateral rectus muscle moves forward, if the eye looks in adduction (see figure) and backwards, if the eye moves in abduction. By this movement, the main muscle action is optimally maintained even in extreme gaze positions.